News

What It Takes to Win a War

Published

11 months agoon

By

James White

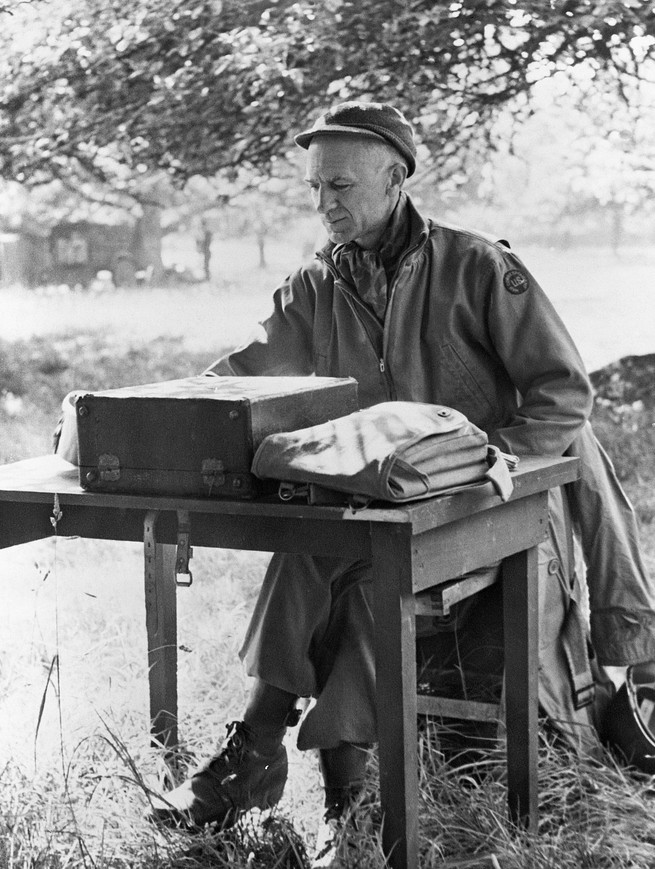

Most war correspondents don’t become household names, but as the Second World War raged, every American knew Ernie Pyle. His great subject was not the politics of the war, or its strategy, but rather the men who were fighting it. At the height of his column’s popularity, more than 400 daily newspapers and 300 weeklies syndicated Pyle’s dispatches from the front. His grinning face graced the cover of Time magazine. An early collection of his columns, Here Is Your War, became a best seller. It was followed by Brave Men, rereleased this week by Penguin Classics with an introduction by David Chrisinger, the author of the recent Pyle biography The Soldier’s Truth.

Pyle was one of many journalists who flocked to cover the Second World War. But he was not in search of scoops or special access to power brokers; in fact, he avoided the generals and admirals he called “the brass hats.” What Pyle looked for, and then conveyed, was a sense of what the war was really like. His columns connected those on the home front to the experiences of loved ones on the battlefield in Africa, Europe, and the Pacific. For readers in uniform, Pyle’s columns sanctified their daily sacrifices in the grinding, dirty, bloody business of war. Twelve million Americans would read about what it took for sailors to offload supplies under fire on a beachhead in Anzio, or how gunners could shoot enough artillery rounds to burn through a howitzer’s barrel. Pyle wrote about what he often referred to as “brave men.” And his idea of courage wasn’t a grand gesture but rather the accumulation of mundane, achievable, unglamorous tasks: digging a foxhole, sleeping in the mud, surviving on cold rations for weeks, piloting an aircraft through flak day after day after day.

We’ve become skeptical of heroic narratives. Critics who dismiss Pyle as a real-time hagiographer of the Greatest Generation miss the point. Pyle was a cartographer, meticulously mapping the character of the Americans who chose to fight. If a person’s character becomes their destiny, the destiny of the American war effort depended on the collective character of Americans in uniform. Pyle barely touched on tactics or battle plans in his columns, but he wrote word after word about the plight of the average frontline soldier because he understood that the war would be won, or lost, in their realm of steel, dirt, and blood.

In the following passage, Pyle describes a company of American infantrymen advancing into a French town against German resistance:

They seemed terribly pathetic to me. They weren’t warriors. They were American boys who by mere chance of fate had wound up with guns in their hands, sneaking up a death-laden street in a strange and shattered city in a faraway country in a driving rain. They were afraid, but it was beyond their power to quit. They had no choice. They were good boys. I talked with them all afternoon as we sneaked slowly forward along the mysterious and rubbled street, and I know they were good boys. And even though they weren’t warriors born to the kill, they won their battles. That’s the point.

I imagine that when those words hit the U.S. in 1944, shortly after D-Day, readers found reassurance in the idea that those “good boys” had what it took to win the war, despite being afraid, and despite not really being warriors. However, today Pyle’s words hold a different meaning. They read more like a question, one now being asked about America’s character in an ever more dangerous world.

Read: Notes from a cematary

The past two years have delivered a dizzying array of national-security challenges, including the U.S.’s decision to abandon Afghanistan to the Taliban, Russia’s war in Ukraine, and the possibility of a Chinese invasion of Taiwan. A rising authoritarian axis threatens the West-led liberal world order birthed after the Second World War. Much like when Pyle wrote 80 years ago, the character of a society—whether it contains “brave men” and “good boys” willing to defend democratic values—will prove determinative to the outcomes of these challenges.

The collapse of Afghanistan’s military and government came as a surprise to many Americans. That result cannot be fully explained by lack of dollars, time, or resources expended. Only someone who understood the human side of war—as Pyle certainly did—could have predicted that collapse, when the majority of Afghan soldiers surrendered to the Taliban. Conversely, in Ukraine, where most experts predicted a speedy Russian victory, the Ukrainians overperformed, defying expectations. The character of the Ukrainian people, one which most didn’t fully recognize, has been the driving factor.

Pyle often wrote in anecdotes, but his writing’s impact was anything but anecdotal. His style of combat realism, which eschews the macro and strategic for the micro and human, can be seen in today’s combat reporting from Ukraine. A new documentary film, Slava Ukraini, made by one of France’s most famous public intellectuals, Bernard-Henri Lévy, takes a Pyle-esque approach to last fall’s Ukrainian counteroffensive against the Russians. The film focuses on everyday Ukrainians and the courage they display for the sake of their cause. “And I’m amazed,” Lévy says, walking through a trench in eastern Ukraine, “that while weapons were not always their craft, these men are transformed into the bravest soldiers.”

War correspondents such as Thomas Gibbons-Neff at The New York Times and James Marson at The Wall Street Journal take a similar approach, with reporting that’s grounded in those specifics, which must inform any real understanding of strategy. The result is a style that’s indebted to Pyle and his concern with the soldiers’ morale and commitment to the cause, and reveals more than any high-level analyses could.

Pyle wasn’t the first to search for strategic truths about war in the granular reality of individual experiences. Ernest Hemingway, who didn’t cover the First World War as a correspondent but later reflected on it as a novelist, wrote in A Farewell to Arms:

There were many words that you could not stand to hear and finally only the names of the places had dignity. Certain numbers were the same way and certain dates and these with the names of the places were all you could say and have them mean anything. Abstract words such as glory, honor, courage, or hallow were obscene beside the concrete names of villages, the numbers of roads, the names of rivers, the numbers of regiments and the dates.

Pyle took this advice to heart when introducing characters in his columns. He would not only tell you a bit about a soldier, their rank, their job, and what they looked like; he would also make sure to give the reader their home address. “Here are the names of just a few of my company mates in that little escapade that afternoon,” he writes, after describing heavy combat in France. “Sergeant Joseph Palajsa, of 187 I Street, Pittsburgh. Pfc. Arthur Greene, of 618 Oxford Street, Auburn Massachusetts …” He goes on to list more than a half dozen others. Pyle knew that “only the names of the places had dignity.” And sometimes those places were home.

As a combat reporter, Pyle surpassed all others working during the Second World War, outwriting his contemporaries, Hemingway included. This achievement was one of both style and commitment. Was there any reporter who saw more of the war than Pyle? He first shipped overseas in 1940, to cover the Battle of Britain. He returned to the war in 1942, to north Africa, and he went on to Italy, to France, and finally to the Pacific. On April 17, 1945, while on a patrol near Okinawa, a sniper shot Pyle in the head, killing him instantly. His subject, war, finally consumed him.

Read: The two Stalingrads

Reading the final chapters of Brave Men, it seems as though Pyle’s subject was consuming him even before he left for Okinawa. “For some of us the war has already gone on too long,” he writes. “Our feelings have been wrung and drained.” Brave Men ends shortly after the liberation of Paris. The invasion of western Europe—which we often forget was an enormous gamble—had paid off. Berlin stood within striking distance. The war in Europe would soon be over. Pyle, however, remains far from sanguine.

“We have won this war because our men are brave, and because of many other things.” He goes on to list the contribution of our allies, the roles played by luck, by geography, and even by the passage of time. He cautions against hubris in victory and warns about the challenges of homecoming for veterans. “And all of us together will have to learn how to reassemble our broken world into a pattern so firm and so fair that another great war cannot soon be possible … Submersion in war does not necessarily qualify a man to be the master of the peace. All we can do is fumble and try once more—try out of the memory of our anguish—and be as tolerant with each other as we can.”

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Source: The Atlantic

NY vs Trump: Judge warns Trump team they’re ‘losing all credibility’ in gag order hearing

Beyoncé shares rare look at her natural hair with wash day routine

UAE: Driverless cars to race at 300kmph at Abu Dhabi’s Yas Marina for prize pool of $2.25 million

D.C. snow underachieved this winter, but some readers saw it coming

New York influencer Eva Evans’ cause of death revealed

How to Follow the WNBA Draft If You’re Newly Obsessed With Women’s Basketball

How to Clear a Stuffy Nose Fast—And Get Back to Breathing Normally

This Easy Addition to Your Egg Muffins Will Double Your Protein at Breakfast

Learning to Swim as an Adult Feels Like Coming Home

17 Comforting Recipes to Bring to a Friend Who Is Grieving

Taylor Swift and Travis Kelce Have a 75% Chance of Announcing Engagement Before September 2024, Experts Claim

How Dolly Parton Dealt With a Bomb Threat Ahead of an Important Concert

Helicopter video: Police pursuit ends with stop sticks, spinout crash

Classified as crime victims, some migrants flown to Martha’s Vineyard get legal protections

Harvard suspends leading pro-Palestinian campus group

Trending

-

News24 hours ago

News24 hours agoWill Lionel Messi play on the turf at Gillette Stadium?

-

News22 hours ago

News22 hours agoZach Roloff Says ‘It’s Time to Move On’ in Teaser for ‘Little People, Big World’ Season Finale

-

News14 hours ago

News14 hours agoChina closing in on laser-propelled fast, stealth subs – Asia Times

-

Tech18 hours ago

Tech18 hours agoBreaking Down the Heroes and Villains of Deadpool & Wolverine’s New Trailer

-

News14 hours ago

News14 hours agoThe Jackson 5’s ‘ABC’ Holds a Chart Record Because of Its Title

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoTom Holland sports a bruise after ‘being hit on the head with a golf ball’ while playing a round at St Andrews

-

News23 hours ago

News23 hours agoWho is Columbia University President Dr. Minouche Shafik? What to know amid campus protests

-

News18 hours ago

News18 hours agoElvis Presley Bought a Complete Stranger a Life-Changing and Expensive Gift